TALK ADDRESSED TO MEMBERS AND FRIENDS OF THE DIPLOMATIC CORPS

My great-grandfather was born in 1874 and died in 1947, eight years after the end of the Spanish Civil War. The societal circumstances that surround his birth and youth are those of Spanish society at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. A novel that I recommend to all of you who wish to know more about the history of Spanish society at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries is Fortunata and Jacinta, by Benito Pérez Galdós. A television series was based on the novel, directed by Mario Camus and starring Ana Belén; in my opinion, it is an excellent adaptation of Galdós’s novel.

In the novel you will see that Spain’s greatest problem was the delayed rise of the bourgeoisie, which, as you all know, is the social class that arose after the French Revolution. The bourgeoisie allowed society to transform itself from being feudal and static (where birth dictated one’s specific social stratum, from which it was very difficult to move) to a society of classes (in which people could move from one class to another more smoothly and freely). It was then that, beginning with the French Revolution and thanks to its transcendental influence, the rest of the European countries opened to change, without the need for revolution. In this context, one can say that the first members of the bourgeoisie, although they were very few, began to emerge in Spain in the mid- and late nineteenth century, as was the case of the family of Juanito Santa Cruz (the protagonist of the above-mentioned novel by Galdós), who were tradesmen. But in Spain, whose civil society had not passed through the Enlightenment in a global, integral way, what the emerging bourgeoisie wanted for their bourgeois sons was to receive a university education, in law if possible, because it was useful in defending their interests without needing to practice. There were very frivolous characters, as was the case with Juanito Santa Cruz, the already mentioned character in Galdós’s novel Fortunata and Jacinta. In this case, one could say that my great-grandfather, born in the bosom of a bourgeois family, was educated as if he were Juanito Santa Cruz, except as he was not at all frivolous, like the literary character, he dedicated his life to sports and art.

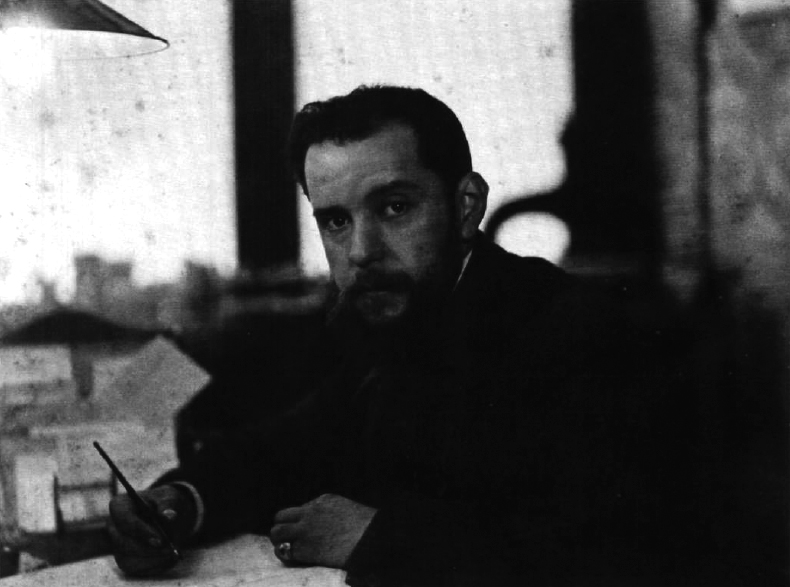

Self-portrait of Vicente Martínez Sanz

In this context of Spanish history, my great-grandfather’s parents were two of the first Spanish entrepreneurs. They owned a factory where they worked with glass and crystal. At that time, the terrible Spanish ill of envy, which has been called the national sport, was beginning to grow among business owners. At that point in time, when my great-great-grandparents already had two children and were expecting a third (my great-grandfather), it was already common in the more industrial provinces, like Cataluña and Valencia, for a business owner to hire assassins to kill other business owners who might overshadow him. My great-great-grandfather, fearing that this might happen to him, said to my great-great-grandmother, who was pregnant with my great-grandfather, “Inés, since I might be killed at any moment, if you want to fight to keep the business for your children, and as you cannot do it alone, I’m asking you to marry Serrano, the factory manager, after a prudent time. He is the only one who can take over for me in managing it.” Unfortunately, what he had feared came to pass, and my great-great-grandmother, although deeply saddened by her husband’s death, followed his advice and after a time married the man he had recommended. Despite the tragedy, and although the child she was carrying (my great-grandfather the photographer) never knew his biological father, she was happy to find that her third and last child – after two girls – was a boy.

Due to personal circumstances, I was very close to my two great-aunts, who had never had children. They knew the man who married my great-great-grandmother as “Grandfather Serrano,” a man who was so close to the family that after my great-great-grandmother died, he lived with my great-grandparents. After all, he was my great-grandfather’s adoptive father, the only father he had ever known. For this reason, Grandfather “Serrano” loved my great-grandfather, the photographer, as if he were his own son. In fact, my great-aunts had always spoken of their “Grandfather Serrano” with praise. Grandfather Serrano was from Salinas, a village in the province of Alicante, and belonged to a wealthy family who would have preferred that their son dedicate himself only to their land holdings. However, this well-loved member of the family’s dreams did not include living only in a village, and as soon as he could, he moved to the closest and most prosperous city, which was Valencia.

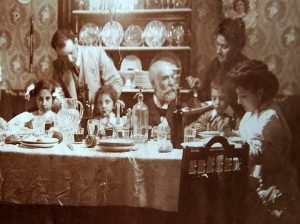

The called Serrano grandfather

Once he was there, he looked for work and my great-great-grandfather (the father of the photographer, who was tragically murdered) hired him to work in his factory. Serrano was an intelligent person, hardworking and, as you can observe later in photos, was also a good-looking man. In this way, as you will also be able to verify in the photos, my great-grandfather had an education which was more Anglo-Saxon than Spanish, an education that he later passed on to his children. In his adolescence, he was an excellent gymnast and practiced a number of sports, among which horseback riding was his favorite. My great-grandfather Vicente received a considerable inheritance from his parents at their death, which was later augmented by Grandfather Serrano’s inheritance. As I commented earlier, the bourgeois social class to which he belonged was educated (here in Spain) to look after their properties without working, but in the case of my great-grandfather, he did not study law as was common with others of his class. Rather, he chose Fine Arts.

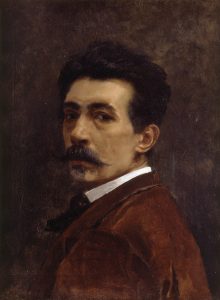

portrait of the painter Joaquín Agrasot

His teacher was Agrassot, a prestigious painter, part of whose work can be found in the Prado Museum. At that moment in Valencia there was a group of excellent painters, but the only one to achieve fame outside of Spain was Sorolla. In the case of Sorolla, due either to good luck or a fluke, a great dealer appeared in his life; this was uncommon at that time, and thanks to his dealer and his excellent pictorial skills, Sorolla becomes internationally known. In fact, as you know, we speak of “the Sorollas of Havana,” “the Sorollas of New York” whose work we have seen in our own country. However, for me, the Sorolla who moves me the most is the one who brings Valencia’s beaches to life, as much for the people relaxing on the sand as for the hardworking fishermen hauling their catch out of the waves with the help of oxen. The influence of Sorolla, who belonged to the generation before my great-grandfather’s, can be seen in some of the photographs; their themes are exactly the same as some of Sorolla’s paintings.

Photography by Vicente Martínez Sanz

As my great-grandfather, following his initial desire to be a painter, studied Fine Arts, had Agrassot as his teacher, who also taught and maintained relationships with some of the most famous painters of his time, such as Ramón Stolz Seguí, Manuel Benedito, Fillol, Beut, and others. He began his career, then, dedicated to painting, given that almost nothing was known of photography in Spain at that time. My great-grandfather counted the painters of the time among his friends . Since the painters of the time, which the exception of Sorolla, struggled to make ends meet, my aunts (his daughters) told me that they believed he felt obliged to help them if they couldn’t pay their bills and that for this reason there were always a great many paintings in their home.

Palette that Vicente Martínez Sanz dedicates to his wife Mercedes

My great-grandfather married very young, and he was very much in love with his wife, my great-grandmother Mercedes. Proof of this was the palette that I still have hanging above my mantelpiece. It is the portrait that he made of her when they were courting in 1883, and on which you can read the dedication, “For Mercedes, from a great admirer of her beauty.” As you will see, it was the curious custom of the time for painters to give their loved ones the gift of a painting they had made themselves on one of their own palettes. One example that you will also be able to see is a palette painted by Beut, another prestigious contemporary painter and friend of my great-grandfather and given to him as a gift. You will see that this palette is a lovely painting of a Valencian alquería (a typical rural home of the bourgeoisie of that time).

Typical valencian farmhouse

As I mentioned earlier, my great-grandmother (the photographer’s wife) was called Mercedes. I am named for her, as was her daughter Mercedes, whose portrait was painted by the prestigious and famous painter of the time, Ramón Stolz Viciano (son of the painter Ramón Stolz Seguí, who was a friend of my great-grandfather).

My aunts Pepita and Mercedes portrayed by the painter Ramón Stolz Viciano

My great-grandmother’s father was the president of a jeweler’s guild who, because he wanted to protect a friend and signed a document that endorsed him, was practically ruined. My great-grandmother, according to the esthetics of the age, was a beauty with several suitors. However, her father, who was an experienced man and had a good eye, knew that he was close to death and made her promise that she would marry “Vicentico” (my great-grandfather) because he was aware of the great love that the young artist felt for her. He also believed that he would be able to die peacefully if he knew she was married to a serious, responsible man who was also wealthy for the time.

The young couple wed and had five children. Without a drop of Anglo-Saxon blood, my great-grandfather taught his children and grandchildren the importance of sports and culture, through the university. He married very young, as he had enough resources to support a family. But my great-grandmother was an ambitious person, in the positive, Anglo-Saxon sense of the word; that is, she wanted to be herself, and was eager to improve her situation. She wanted to start a business and run it herself (something that was unusual for a woman at that time in our country). Because she came from a family of jewelers, with a father that had been the guild president, but who had died impoverished, my great-grandmother married my great-grandfather and he also took charge of a younger sister who had been orphaned, and who he cared for as if he were her father.

My great-grandmother was a woman who, although she followed all the customs of her time, had a completely modern way of seeing the world. She pestered her husband so much about having her own business that even though he did not agree, he found himself forced to agree out of love. The business sold “earthenware, crystal, and porcelain,” all of the finest foreign brands, and was located in Paz Street, which was the most commercial in the city. However, in those days it was mandatory for the husband’s name to be on the business, so as not to shock all of Spanish society, which would have been frightened to contemplate a businesswoman. My great-grandmother, as I said earlier, was woman with ambitious dreams, and she ended up having the most important business of its kind in a city that was beginning to grow. It’s curious that the word “ambitious” in Spain often has negative connotations; nevertheless, as you know, it is a positive term in Anglo-Saxon culture because it means a person wants to better herself.

My great-grandmother’s business in the center of Valencia

As well as being a businesswoman, my great-grandmother was also a very loving mother, something I have always heard in my aunts’ voices. My great-grandparents had five children, and my mother was the daughter of one of their sons, all of whom were brilliant at their professions. The women (my aunts) were awarded the special prize for singing and piano, and the men (my uncles) also excelled in their university careers. My grandfather (their fourth child) was awarded, among other prizes, the Ramón y Cajal prize; he ended up working for the United Nations and was a UNESCO expert.

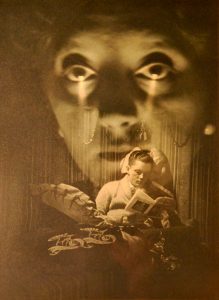

Photomontage vision with José “Pepe” Martínez son of the photographer

After my uncle Vicente, the oldest of my great-grandparents’ children, and my two aunts Mercedes and Pepita (who had no children), Inesita was born. She had the great misfortune to die at only six months of age. My great-grandmother was inconsolable and when her friends, trying to soothe her, said, “Mercedes, you have three children and you will most probably have more,” she would reply, “No child can substitute for another.” I believe that it was at that moment of weakness that she convinced her husband to open the famous shop that she had been longing for. Later, her last two sons were born, Pepe (my grandfather) and my Uncle Alberto.

My great-grandmother’s business quickly became the most important shop for buying earthenware, crystal, and porcelain in the city; however, one day she returned home from the shop, sat down on her bed, and said, “I feel terrible.” No sooner had she uttered the words than she died. We have never known what she died of. My aunts say that, thank God, she didn’t know that she was dying. Her death left an inconsolable husband and five children. The oldest, Vicente, was 16. Mercedes was 15, Pepita was 12, and the two youngest: Pepe (my grandfather) was 4 or 5 and little Alberto was 2.

Because my great-grandfather was so sad and depressed after my great-grandmother’s death, the first thing he did was to close the family business. He didn’t have the strength to sell off the remaining merchandise, and so he gave away much of it and distributed the rest among the family. My mother still has many pieces because since my aunts had no children, they acted a bit like my mother’s mothers, as they were later mine.

From then on, for my great-grandfather there were only two important things in his life: his children, and painting, which he did as an amateur. My great-grandfather painted well, but he wasn’t content with his achievements; it was thus that, as my Aunt Pepita said, “He found an expensive mistress – photography.” In those days it was expensive because everything had to be imported from abroad, given that the necessary material was not available in Spain. As a photographer, he was awarded many first prizes in international photography shows, as his medals from different countries proved: some were silver and some were gold, and when they arrived, my Aunt Pepita (the younger of his two daughters) said she saw that often, this man with great control over himself, teared up when he saw them. My grandfather also told us that there were often three sections in these expositions: one for portraits, one for landscapes, and one for photomontage, and that occasionally my great-grandfather received the first prize in all three categories.

In this way, my great-grandfather gave himself fully and passionately to the art of photography. As my father, the writer Vicente Puchol, tells it in the prologue he wrote for an exhibition that was held in Valencia in 1985, in what is now the headquarters of the Bancaja Foundation:

“When Martínez Sanz began to work as a photographer, the art form was still in its infancy; its techniques were as ghostly as they were rudimentary, and he was obliged to improvise materials and instruments that did not yet exist, making use of a mysterious innate skill. At the beginning, photographic negatives were large glass plates, held in a frame; lenses were up to 15 centimeters thick; cameras were mounted on cumbersome rolling tripods, and the artist was obliged to disappear under a heavy black cloth in order to compose the shot. It was risky to leave the studio with so much baggage if one did not wish to be subject to innumerable calamities, not to mention public derision. But Martínez Sanz was dedicated to his art; he was so devoted to photography that he was able to blend in with the populace, and to convince strangers on the street to enter his studio, where he captured the profoundly moving expressions of their inner life that hid behind their everyday faces.”

Portrait of the dulzainero by Martínez Sanz

Among the highly favorable press clippings that I have about my great-grandfather, I would like to bring up an anecdote from one of them which is about one of his most famous photographs: the dulzaina player.

It happened that one day my great-grandfather brought an old man with an abundantly wrinkled face to his studio. He was a dulzaina player by trade – the dulzaina is a typical Valencian woodwind instrument – and a very sarcastic smile was always playing on his lips. My great-grandfather dressed him in typical Valencian clothes and posed him so that he appeared to be playing the instrument. But because the model’s attitude wasn’t what he was looking for, because his pose was “artificial,” in the sense that it seemed he wasn’t actually playing, my great-grandfather finally said, “Play! Play with real passion!” The dulzaina player blew into the instrument with such force and passion that the sharp, high note suddenly filled the tiny porch and invaded the stairway, entering doors and windows without permission. As a result of the unexpected “concert,” the neighbors kicked up a fuss – a real scandal – leaning out of doors and balconies, unable to discern the source and the reason for the happy music. My great-grandfather, while the neighbors’ curiosity and the dulzaina player’s music continued, took a number of plates whose prints provided an example of spontaneity and good photography.

Thus, one of my great-grandfather’s specialties was the portrait in which he was able to stand out in such a way that his prints were always praised. He set up a studio in an attic in his house where he enjoyed photographing his children in the most varied costumes. Although some of the subjects who climbed up to his studio were popular personages, other times he photographed his own family or well-known people. He photographed my Aunt Mercedes without any costumes or props, and did the same with my Aunt Pepita, but when he wanted to capture them in character, he tended to dress Mercedes as a gypsy or a woman wearing a mantilla. Pepita was often dressed as the Virgin, even as the Virgin as a girl, when she was 12 or 13 years old.

My aunts Mercedes and Pepita characterized

At the same time, my great-grandfather was, with J. Ortiz Echagüe, one of the photographers who expanded pictorialism in Spain, which they expressed through numerous landscapes and portraits.

Pictorialism is the name given to an international style and aesthetic movement that dominated photography during the later 19th and early 20th centuries. There is no standard definition of the term, but in general it refers to a style in which the photographer has somehow manipulated what would otherwise be a straightforward photograph as a means of “creating” an image rather than simply recording it.

The pictorialist movement attempted to blur the boundaries between painting and photography making them much more permeable. It is for that reason that many pictorialist photographs appear to be authentic paintings.

Photography by Martinez Sanz

Typically, a pictorial photograph appears to lack a sharp focus (some more so than others), is printed in one or more colors other than black-and-white (ranging from warm brown to deep blue) and may have visible brush strokes or other manipulation of the surface. For the pictorialist, a photograph, like a painting, drawing or engraving, was a way of projecting an emotional intent into the viewer’s realm of imagination.

Like a painter, Vicente Martínez Sanz composed new landscapes, using a combination of lights, shadows, and mists. He carried his heavy camera to the banks of the Albufera (a sort of lake, near the sea, located in the outskirts of Valencia), or to the Salinas region of Alicante, where he owned a rustic property.

My grandfather used to tell us how, when he was about ten years old, he accompanied his father in order to help him carry all of the camera equipment and how often they would wait for three or four hours until his father felt that the time was right, according to the light, to capture a landscape.

As my father, Vicente Puchol, says in the prologue of the catalogue for the Valencia exhibition:

“He reproduced humanity’s pathways, homes, and horizons with reflective shadings. Also worth noting are his studio compositions, based on psychological themes, and those that with surprising anticipation depict Bergmanesque landscapes; they lead one to wonder what the artist would have produced had moving pictures been common at that time. Without ever leaving Valencia, he was in contact with artistic photography movements around the world, and even more surprisingly, was in their vanguard. He was the first photographer in Spain to work in color, using the three primary colors impregnated in grains of starch. Nevertheless, we know little of his work in the laboratory, how he perfected the techniques then in use, or of his method for applying a lyrical transformation to his images. His photographs demonstrate a mastery of framing and focus, and precision in capturing light, as swift as time itself. He combines reality’s diverse elements in order to extract a purer and more significant reality. The rest, as is common to artistic genesis, belongs to its creator’s untransferable, intimate world.”

At the end of the war, my great-grandfather, who had never participated in politics, entered a sort of depression, thinking, “in a civil war there were no victors and no vanquished, given that everyone had been vanquished.” My mother says that all of my great-grandfather’s children visited him in the evening after they had finished work. Seated at a large round table, they would talk. My mother also recalls that many of these conversations began by remembering the time before the war, and that she had thought that before the war, Spain must have been a kind of “heaven on earth.” Nevertheless, one day my grandmother showed her a photograph that shook her. My grandmother thought that this photo truly reflected that there were two Spains before the war: one in which its people ate, and one in which they did not. This photograph, which I will show you later, was not taken by my great-grandfather, but I believe that it is interesting from a historiographic standpoint because it reflects a difficult and sad social reality.

Spain in black and white

At the end of the Spanish Civil War, my great-grandfather abandoned photography, and withdrew from an environment that was unfamiliar to him; he limited himself to recording his family’s private moments – as it happens, his final photograph was of my mother. The Valencia Photo Club made him its president, holding a collective exhibition which showed his work alongside that of other Valencian artists. He died in 1947.

Mercedes Puchol Martínez

Madrid, January 2015